On These Past 3 Weeks of Volunteer Work

London Design Festival is a citywide annual event that takes place around 9 days every September to celebrate the diversity of design. I remember back then in 2016 I was helping my former workplace preparing for their collaboration project with the Indonesian government to be submitted to the first ever London Design Biennale (which is a part of LDF), and visiting the Biennale has been my goal ever since. Now, I declare that I am beyond excited for not only be solely a visitor for this year’s Biennale, but also as a volunteer staff who helps around and gains specific, deep knowledge about the event. Additionally, I extend my volunteer work up to 3 weeks so that I can experience more events and places such as Global Design Forum 2018 (and roaming the V&A after dark, haha).

How does this volunteer work has something to do with my ongoing project?

I present to you my highlights:

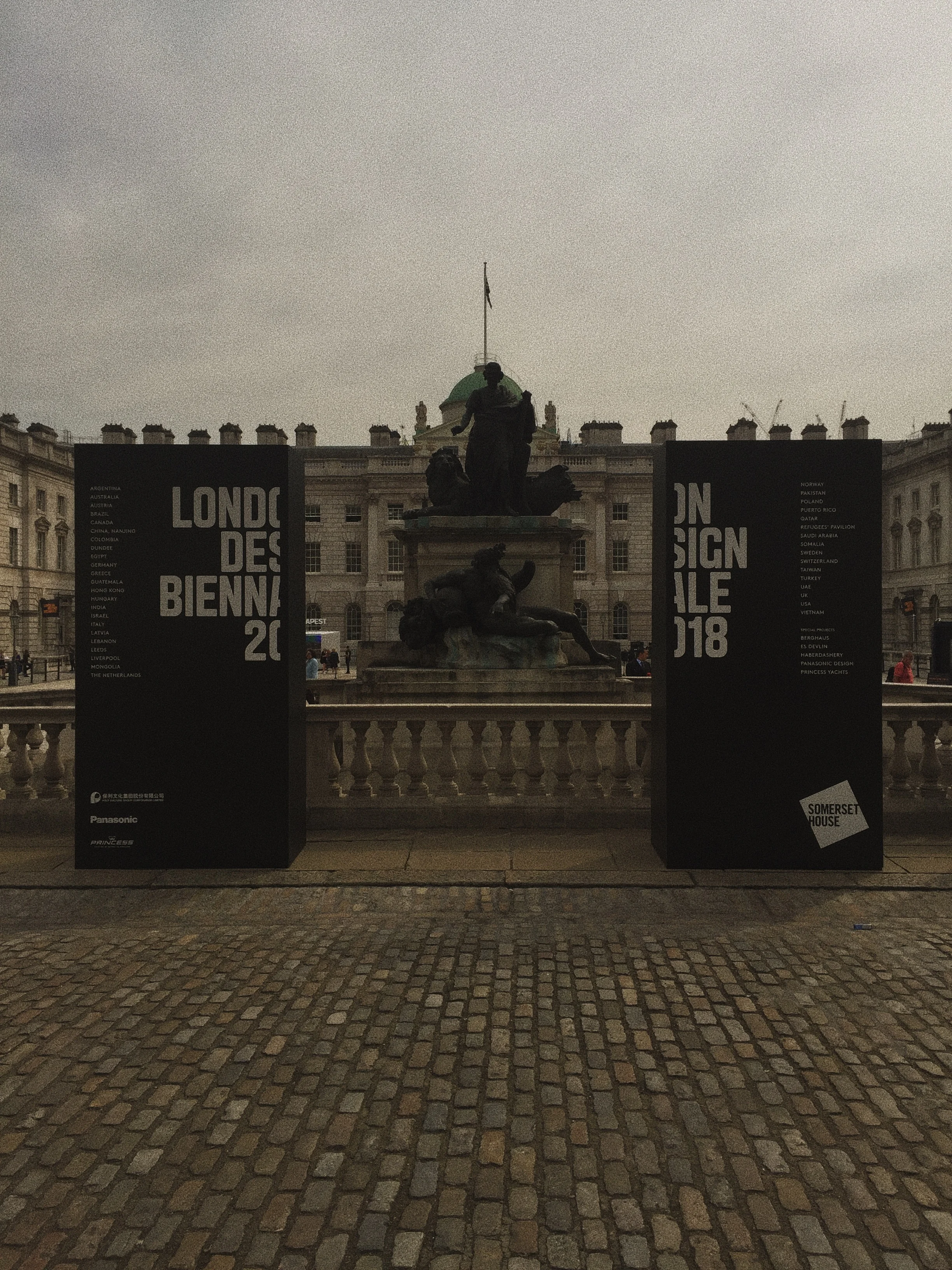

London Design Biennale 2018

I am so delighted to join as the two-weeks volunteer for one of the biggest design exhibition in London (or maybe in the world!): London Design Biennale 2018 at Somerset House. This event gathers up some of the most ambitious designers, innovators, and curators across six continents.

That means, a big, fat chance for me to get feedbacks from notable experts and stakeholders.

Speaking of this year's theme, Emotional States has been chosen for the biennale participants to interpret. The results are numerous immersive and engaging installations from 40 countries that interrogate how design affects every aspect of people's live and exciting examinations of the relationship between design, strong emotional responses, and real social needs. Here are some of the amazing projects that I came across, and how I can reflect on it into my current project.

Egypt – Modernist indignation

The Egyptian installation mourns the loss of the country’s modernist architecture, a rich heritage that has been left to ruin or violently erased, and asks the question: how can a design language that was once embraced by a society be so easily forgotten and denied a place in history?

Visitors will see a contemporary reinterpretation of a fictional 1939 exhibition put on by the editors of Al Emara, the first Arabic-language design magazine, which was published between 1939 and 1959. The original exhibition would have explored the magazine’s mission, but now it stands as a testament to a lost culture, says curator Mohamed Elshahed. “In the absence of accessible archives for the study and documentation of modernist architecture in Egypt, the magazine, scattered between private collections and antique booksellers, is the most comprehensive record of the country’s embrace of modernist design. Many of the buildings published in the magazine have been demolished, mutated or suffer from poor upkeep and no heritage status has been granted to any structure of modernist design.”

This ambitious project from Egypt is something that I can heavily relate to my project: it’s about design (in their case it’s about architecture) as a cultural heritage and the fragility of it to be forgotten, or destroyed violently. The project points out about the importance of record or archive to “save” the said design, in which they present as a visualisation of what could’ve been an exhibition held from the perspective of Al Emara magazine in 1939.

Colombia – Triada

Colombia is a country whose recent past has been framed by armed conflict and violence related to the drug trade. David Del Valle, curator of the country's first entry to London Design Biennale, explains that this has created a largely negative impression of its culture and society. “Colombia is a country full of prejudices, many of them erroneous, others true, but the vast majority exaggerated,” he says.

In response to this, Del Valle has created an installation that juxtaposes the emotional states that exist in a country that does not deny its troubled past, but refuses to be defined by it. “Our installation makes reference to two realities: the pain and shame that Colombians feel about the armed conflict; but also the happiness and pride they have for their country and the opportunity we see with the peace process.” The installation is called Triada (or Triad in English), in reference to the emotions of pain, pride and happiness. A circuit has been designed allowing people to journey from negative to positive states, exploring sounds and images that will make them feel a range of sentiments. “We want visitors to focus on their feelings in a space where aesthetics, images and sounds try to showcase the reality of a country,” says Del Valle. The images and textures on display are all inspired by traditional manufacturing techniques that are unique to the country. “We want visitors to take away the image of a country that is moving forward, highlighting the positive emotions that we, as natives, recognise and feel.”

I had a pleasant conversation with Del Valle himself during one shift at the area explaining the two paradoxical emotions emitted in response to Colombia history where he came from. I said that it was something that I experienced when revisiting my own country’s history that are tend to be denied and something not to be discussed. My project revolves a lot on revisiting the past, being honest with my own identity, and learn from it. It gives me courage to do something that never been done before.

Del Valle also gave me numerous technical advices on presenting my research. His team did an amazing augmented reality (using the Unity software) presentation for the exhibit to increase the audiences’ engagement to the visuals and the subject matter, something that I’m considering right now for my the presentation of my project later on.

China, Nanjing

The Chinese pavilion considers the emotional significance of an iconic structure and how it became part of the nation’s collective memory. The Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge was completed in 1968 during the Cultural Revolution and was the first modern bridge in China to be designed and built without foreign assistance. At more than 4.5km in length, the double-deck roadrail bridge quickly became a national symbol of technological achievement, its image and the story of its construction disseminated through mass media, such as propaganda posters and lowcost photography. “The bridge is an exceptional case of a single monument which in the radical 1960s and 70s sparked an emotional state among a whole nation,” explains curator Andong Lu. “It became the pinpoint of a shared memory and people from all over China had their own stories to tell about it.” The exhibition explores how this collective memory came into being, revealing to visitors a historic space that is both real and imagined. Since 2014, LanD Studio has collaborated with historians and local artists on the Memory Project of the Nanjing Yangtze Bridge, amassing an archive of artefacts, memories and audio and visual evidence – a selection of which is on display at London Design Biennale.

Perhaps, this project is the closest direction that I wanted to be implemented into my project. It’s about collecting fragments of collective memories in a form of visuals and then synthesise it so that others can benefit from it. I was having this initial idea of collecting artefacts from public domain, which could be so much easier for my case since the nature of Indonesian visuals are more of ephemeral rather than organised and archival.

Puerto Rico – Soft Identity Makers

“State” is a word loaded with emotional significance in Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the USA where inhabitants can call themselves American citizens but have no voting rights. For some, “state” represents the ideal of full annexation to the USA; to others, it expresses a yearning for independence and the fight against an imperialist master. In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which left much of the island in ruins, these questions of identity have become more pressing: what do “state” and “nation” mean when you are forced to be a refugee in your own country?

The Puerto Rico Pavillion is a timely exploration of these ideas of nation and identity, and the symbols that represent us. “How many times have you felt that your shield, flag, or passport isn’t representative of your identity? How can we define a contemporary national identity?”, ask Miguel Miranda and Celina Nogueras of Muuaaa. “Even though these symbols are rigid, our identities need to be malleable; they are soft.”

This project talks about national visual identity, something that I put into my questions not long ago, before I changed it into my current question. Perhaps this project came up with the same question I always have in my mind: if Indonesia is in abundance of visuals and ephemeras, why are we struggling finding our own national visual identity? This project also putting me into the realisation to have the ability not only to collect all of the existing visuals but also the ability to synthesise the signifiers inside of it.

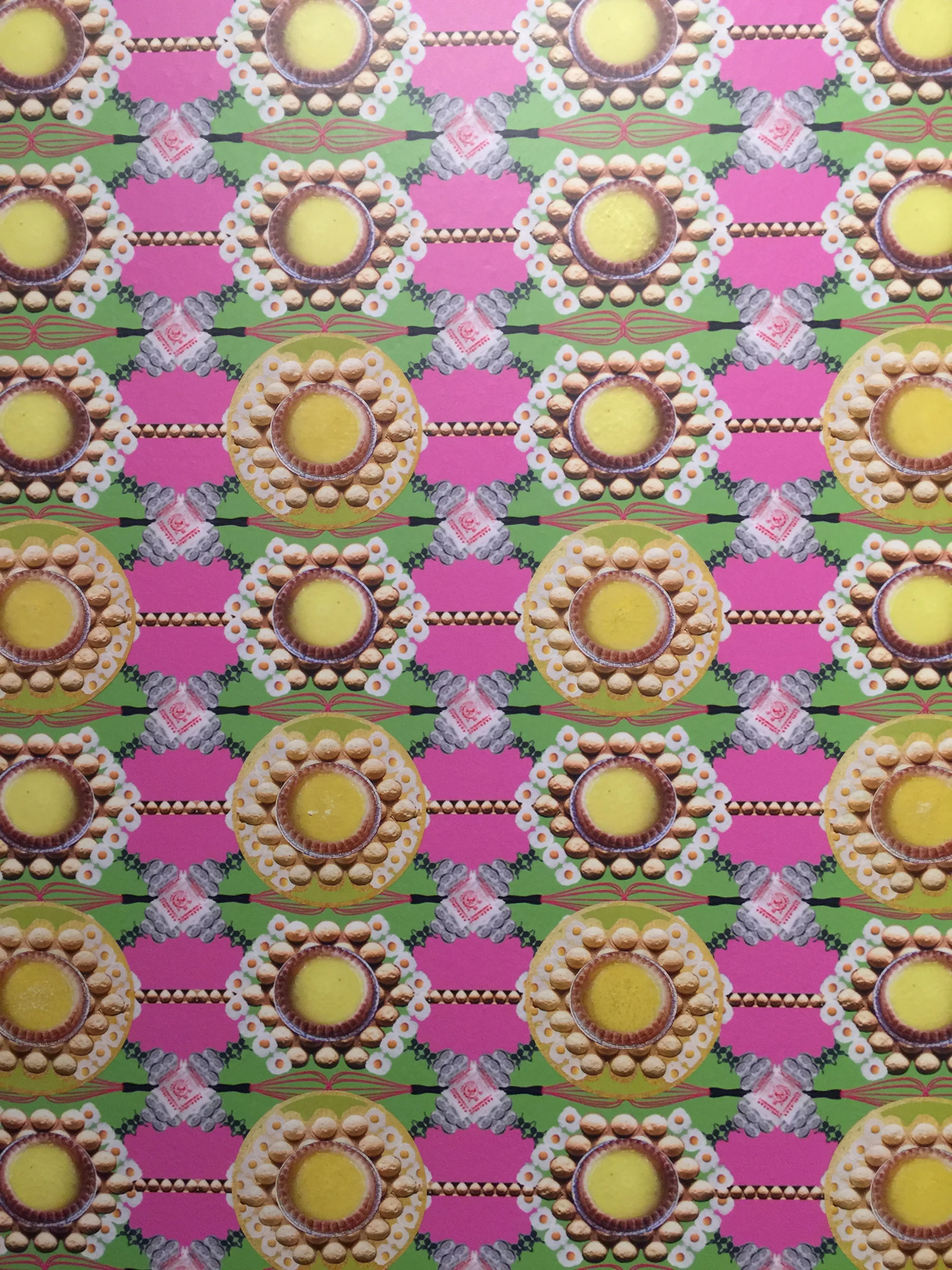

Hong Kong – Sensorial Estates

Why is smell so evocative of memories of a time and place? How do aromas resuscitate so vividly our dormant emotional states? The Hong Kong entry, Sensorial Estates, seeks to explore this realm of Proustian rushes from time past.

In the transient, fast-paced, sub-tropical metropolis of Hong Kong, the scents tied to its identity are as varied as its constantly changing population and landscape. “We’ve created an aromatic journey that blends stories about the emotional connection of aroma to food cultures, cha chaan tengs [Hong Kong diners], worship and the very origins of the meaning of the name Hong Kong – which translates as ‘Fragrant Harbour’ – within personal and collective memories,” says curator of design objects, Elaine Young. “We hope to remind visitors of the power of smell as a transporter and time machine. Visitors are invited to experience more about the design objects by visiting the space.”

Some Other Amazing Discoveries & Feedbacks

Amazing feedbacks doesn’t always comes from people you’re considering as an experts or gatekeepers or whoever has the power on certain subject, but also a colleague. In this volunteer work, I met Sini, a fellow MA student from Macau studying at King’s College London who just finished her MA dissertation about, guess what, digital preservation and curation. She’s enrolled in Digital Culture and Society course, a subject I never heard before (and didn’t know exist as a university course).

I pitched my project to her and asked for some feedbacks. The most powerful insight that I got from her is probably how I have to be really specific on my curation project, followed by her giving me this powerful social curation canvas that is absolutely helping me to figure our specific aspects needed for my project. The other plus point is, this chart helps me communicate my ideas to my collaborators when testing my intervention and to my stakeholders when asking for feedbacks.